There’s a weird trap I’ve noticed a lot of people, including doctors, fall into. They try to determine if drugs are good or bad without considering what it is they’re trying to accomplish.

I saw this most recently with the debate over the legalization of psychedelics in Massachusetts. If you read my voter’s guide to the MA ballot, you’d have seen that Question 4 regards whether Massachusetts should legalize the growth, possession, and use of certain psychedelics, as well as the creation of licensed “trip” facilities. In my voter’s guide, I reluctantly recommended against it, but I could see the argument either way.

Most of the debate over this question ended up being over whether or not psychedelics are “good”. Good being a subjective term, this quickly went to the “objective” question of whether psychedelics are helpful for mental illness. Proponents of psychedelics pointed to the studies on psychedelics’ positive effects on depression and PTSD (the latter of which, have, unfortunately, gotten a lot cloudier recently). Opponents of psychedelics pointed to the risks of psychosis and driving under the influence. Neither side could agree whether psychedelics are good or bad.

That’s why it came to me, a random blogger on the Internet, to say this: both sides are right and neither are right. Asking whether psychedelics are good is asking the wrong question. Ask, instead, what psychedelics do. As anyone who’s ever taken psychedelics knows, they alter your perception, sometimes in profound ways. Once you are on them, your perception is altered for the duration of the trip, and that can have lasting influences on your outlook and perception of yourself afterwards.

If you are severely depressed, having an altered perception can be good, as your normal perception is bad. If you’re someone with an already tenuous grip on reality, altering your perception can be bad. If you’re driving, altering your perception is really bad because you need to see the road. Psychedelics, in and of themselves, are neither good nor bad. They just alter perception.

Maybe this seems obvious to you. But I see this mistake come up in medicine again and again, and not just in psychiatric medicine. Take rapamycin, for example, everyone’s favorite longevity drug. Rapamycin inhibits growth, among other effects. This is neither good nor bad. It just is. If you are trying to prevent liver fibrosis, rapamycin is good. If you are trying to recover from an injury, rapamycin is bad.

Lifelong rapamycin is, net-net, for most people, probably bad, even if you avoid rapamycin’s other effects like hyperinsulinemia. That’s because preventing growth is generally bad, as most of the body’s processes that involve growth are health-promoting, even though organisms with less growth (e.g. calorie-restricted organisms) tend to live longer. If you sprain your ankle or are trying to build muscle to help back pain, you want to be able to grow.

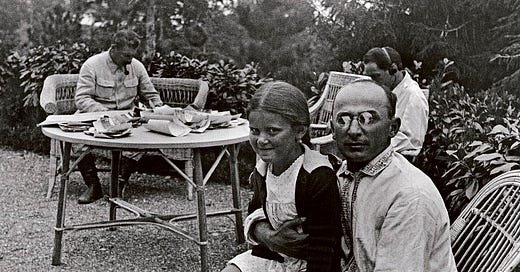

I’m not the first one to have noticed this. It was as early as the 50s that scientists thought to use a rat poison, called warfarin, that caused profuse bleeding to prevent dangerous blood clotting, or thrombosis. Warfarin is bad for you if you’re a rat who eats too much poisoned cheese or possibly if you’re Joseph Stalin. Warfarin is good for you if you just had a stroke and you’re worried about having another one. Warfarin just causes bleeding. Whether that’s good, bad, a mechanism of action, or a side effect, depends on what you’re trying to do.

I guess what I’m trying to say is that I’m tired of hearing about “beneficial drugs” or “side effects”, or even “longevity-promoting drugs” or even drugs that “reduce all-cause mortality”, like apparently Adderall does. Drugs are tools. They act in certain ways and in certain pathways. Sometimes they act in multiple different pathways. We have to figure out for ourselves whether this is something that we want.

One man's medicine is another man's poison