A lot of people think that predictions of when AI will achieve certain milestones are important. Given the rapid rate of AI progress and the lack of unified safety standards, I’m inclined to agree. We need a deadline for safety and ethics standards for AI that can clearly be communicated to industry, regulators, and the public. Put another way, by the time a harmful AI is developed, it’d be best if the generals in charge of our nuclear arsenal aren’t caught off guard.

I also think that the development and communication of these predictions would be a perfect opportunity to also develop and communicate reports of what impact AI is having right now and how we can mitigate the harmful effects of AI. Any regulator, when presented with a prediction of when AI will reach human intelligence, is likely to say, “Ok, but what should I be doing about that today?” It’d be good to have clear answers.

Unfortunately, right now, I think the AI prediction community is headed down the wrong path towards accomplishing these goals. The community is way too focused on developing new, individual theories, rather than developing consensus data and models. The result of this has been pages upon pages of long missives arguing about the rise of AGI, but no real progress on predicting it, or at least no progress that everyone can agree on. And contrary to the efforts of some recent funders, this is not a problem that can be fixed by just adding additional monetary resources, like the FTX Future Fund’s recent $1.5 million competition for predicting the dawn of AGI (even though I appreciated the chance to win some of it with my last blog post).

These efforts don’t fix the problem because the problem isn’t a lack of words. There’s been a lot of writing of a lot of words. The issue is the content of the writing. It’s all individual models and theories on a small basis of facts. Not only have these theories far outrun the facts, but the lack of consensus models means that nobody can even agree on what facts are missing. At this point, even if someone did correctly predict the rise of AGI, nobody else would believe them and they’d be drowned in a sea of counterarguments. This problem doesn’t change if the correct prediction happens to be chosen as a winner by the FTX Future Fund.

It doesn’t have to be this way. With the resources of the FTX Future Fund (*cough*) and the combined brainpower of the LessWrong/EA posters, the AGI prediction community could create a report in the next 6 months that would create a solid, factual basis for AI predictions. This report could also:

1. Point to where more data is needed

2. Establish consensus models to predict AI progress

3. Establish what impacts AI is having right now

4. Establish how people might mitigate the harmful impacts of AI now and in the future

5. Communicate all of this clearly to technical and non-technical audiences

Get a couple big names to sign off on this report, and it could be the consensus report that everyone refers back to and builds off of. When policymakers want the “expert opinion” on AI, they could go to this report. When a scrappy young blogger wants to fill in the gaps on AI mitigation, he could send an email to the maintainers of the report. When a new technique is developed that changes everyone’s AI timelines, one of the models in the report could just be tweaked. When a newspaper editor wants to run an opinion piece on what impacts AI is having right now, he could just assign one of his writers to read the report.

This might all seem like a pipe dream to you. You might think that the field of AI is too immature or changing too fast for a report like this. I’d say the opposite. I think precisely the point at which the field is so exciting and dangerous that philanthropists are spending millions of dollars on it is precisely when there needs to be some kind of consensus. Otherwise, we have no idea what we’re spending money on or what to be worried about.

There’s historical precedence for this. This isn’t the first time a bunch of nerds have worried about an existential risk for humanity as the rest of the world yawns.

Let me take you back to the year 1986. Reagan was selling weapons to Iran, Chernobyl had just melted down, and Steve Jobs had just founded Pixar. The world was in a dark place. Thinking even darker, warmer thoughts were the founders of the burgeoning field of climatology, who had started to really worry about greenhouse gasses. They knew that industry was releasing increasing amounts of carbon dioxide every year, and they worried about the potential for catastrophic levels of global warming. They thought that it was possible that this warming would start affecting life on Earth very soon, and that it was important to come up with a scientific consensus on what was happening and what was likely to happen next.

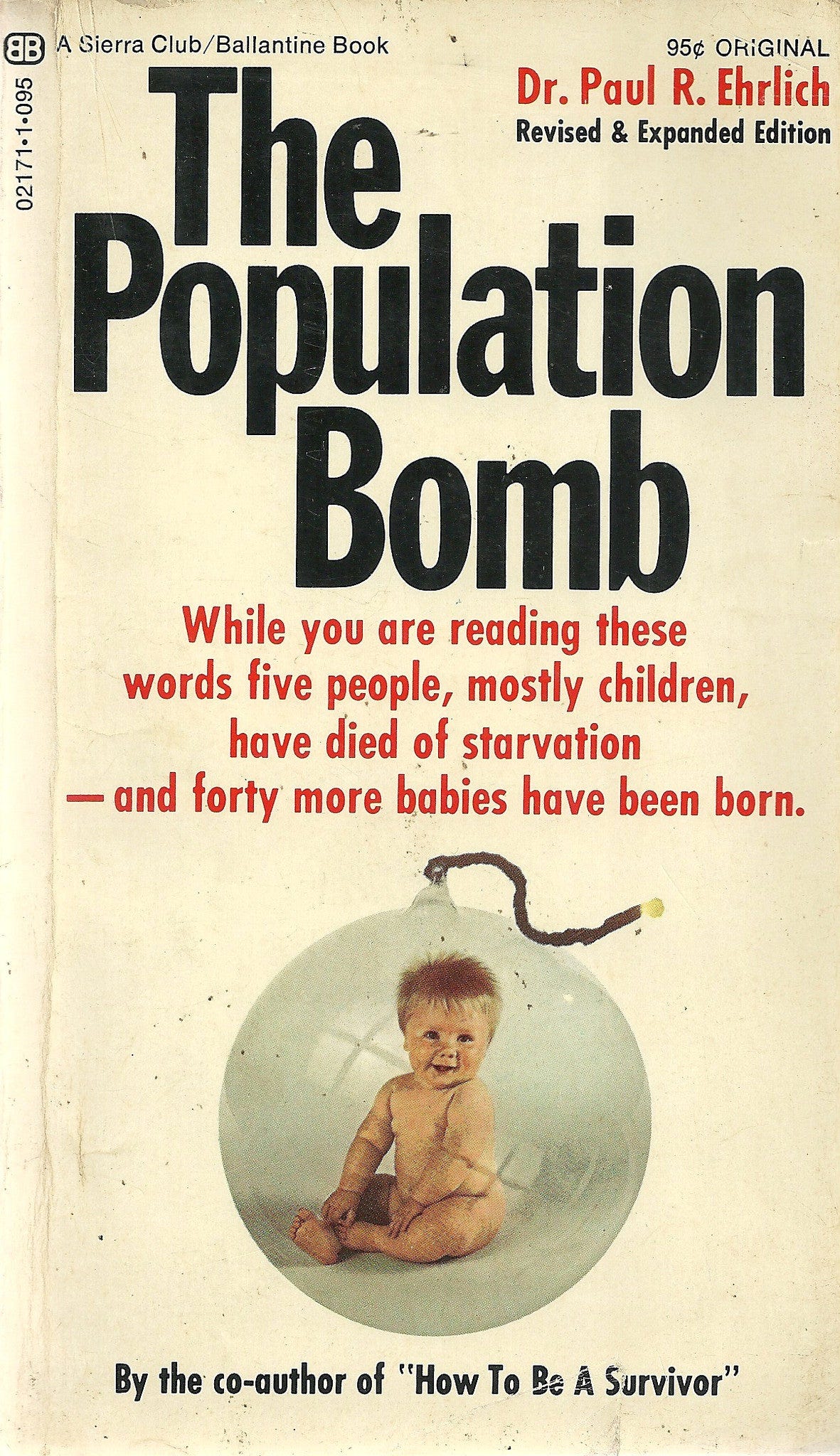

It’s important to note that this was not a consensus worry at this time. The public had spent the 1970s being warned about “global cooling” and “the population bomb”, both ideas backed by prominent scientists that had come out to nil. Meanwhile, even among physicists and meteorologists, the idea that carbon dioxide would stick around in enough quantities in the atmosphere to cause global warming was controversial.

Really, there were only three big, broadly known pieces of evidence that made these scientists confident in the reality and dangers of global warming:

a. the “Keeling curve”, started in 1958, showing steadily increasing atmospheric CO2 levels

b. Suess and Revelle’s 1957 data showing that the ocean had absorbed most atmospheric CO2 up to this point, and that the ocean had a limited buffer factor to absorb that much CO2

c. Gilbert Plass’s 1956 model showing the effects of CO2 on global temperature

Those were pretty much it. There were a lot of unknowns! Even by the time the founders of climatology had organized themselves enough to produce the first Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, report in 1990, there were still so many unknowns that the first report plainly stated, “The size of [global] warming is broadly consistent with predictions of climate models, but it is also of the same magnitude as natural climate variability.” In other words, it was still impossible to separate the signal from the noise.

Fast forward to today and things are very different. The field of climatology, prompted in big ways by the IPCC, can state confidently both data and predictions about past global warming, future global warming, impacts of global warming, and how we might mitigate those impacts. There are still disagreements and unknowns, but the map of climatology has been broadly filled in, and the disagreements are mostly about the details rather than the broad strokes.

Most importantly, top newspapers regularly report in depth what the IPCC has to say, and policymakers around the world listen. There is no top government official of a major country who has not at least read either the IPCC or a report of the IPCC report. It has made a huge difference to climate negotiations.

I think that the AGI prediction community could take a lot of lessons from the IPCC experience. The IPCC used its role as a synthesizer and communicator of climatology research to create a world-renowned resource for climate change information. It was also able to direct research towards underexplored topics, which was helpful for the field as a whole.

Now, the IPCC of course has some advantages that any AGI prediction community would not have. It’s a UN-affiliated organization, lending it some gravitas; it’s composed of many of the world’s top scientists and working with a field that’s thoroughly academic, so there’s academic rigor built into its work; and it has an $8.5 million endowment sponsored by the member countries.

But it also has disadvantages that no AGI prediction community would have. It’s a UN-affiliated organization, meaning that there are parts of it that are entirely dysfunctional; it’s composed of many of the world’s top scientists and working with a field that’s thoroughly academic, so any and all critiques of academic science apply; and it has an $8.5 million endowment sponsored by the member countries, so every oil-producing power can easily mess with it. Also, because of the conventions of academic science, the authors of the IPCC can’t even get paid (don’t ask where the $8.5 million goes).

And, most importantly, the IPCC had to blaze a trail for consensus prediction making. Before the IPCC, there was nothing really comparable to this massive, multi-disciplinary, multinational report. The IPCC had to discover a lot of the best practices for making this kind of report entirely on its own. The AGI prediction community, by contrast, can copy those best practices wholesale.

And what are those best practices? I’m glad you asked!

First of all, from the beginning, the IPCC didn’t just write a report with their predictions alone. They had and have multiple parts to their report:

1. The physical science basis, which explains why global warming is happening, what the amount of climate change will be in the future, and timelines for the change. In this section, the timelines for change are built from the ground up, with every assumption and piece of data in the final model clearly stated and supported.

The report also discusses a range of timelines depending on changes in assumptions (e.g. warming in the year 2050 if carbon emissions peak in 2020 or 2040). This not only incorporates a range of viewpoints on things that reasonable people can disagree on, it also makes it easy to compare predictions over time. People in 2040 will be able to use the model from 2020 regardless of when emissions actually peak.

2. Impacts and adaptation, which explains what the effects of global warming are on the things that matter to humans, like crops, coastline, and weather, and explains what people can and are doing to mitigate these effects. Again, these impacts and mitigation strategies were built from the ground up as much as possible.

3. Later on, special reports were added as deep dives on topics of particular interest. In the most recent report, these were topics like how warming can be kept to 1.5 degrees Celsius and how the oceans are changing today in response to warming.

There are obvious parallels to AGI prediction. As I discussed in my previous essay, at bare minimum, all AGI predictions need to be built from the ground up. I don’t need to agree with someone who says AGI will exist by January 1, 2043, but I should be able to follow their reasoning. We should be working off of the same data, and, if I accept their assumptions, I should come to their same conclusion.

Also, AGI predictions should be made in conjunction with discussions of the current and future impacts and adaptations of and to AI. AI is already affecting our world, and people are responding to it differently. Decision-makers should have realistic expectations of how AI has impacted us and will impact us, so they know what to think about the AGI prediction.

As an added bonus, combining AGI predictions with discussions of the impact and adaptations of people to AI forces dialogue between predictors and the people who are or will be dealing with AI in their work. This is a good thing. At some point, everyone is going to have to face an impact of AI on their daily life. It’d be best if they were prepared for this (i.e. by having a serious conversation with someone who thinks about AI all day, every day). The alternative is to have the generals in charge of our nuclear arsenal waking up one day and suddenly realizing that they have a new adversary that they don’t remotely understand.

Speaking of dialogue, the second thing that the IPCC did really well from the beginning is make sure they communicated to scientists, politicians, and the public at large. Every report has a summary for policymakers as well as a more detailed report for scientists. The summary for policymakers is simplified and focuses on key takeaways, but points to the sections in the detailed report with additional information. The most important findings are communicated to the public through press releases and interfacing with journalists.

This avoids the “inside baseball” problem that so often faces predictors of AGI. Right now, there’s limited communication between people who work on AI and people who worry about AI, and there’s no communication between either of those groups and policymakers or the outside world. This, again, raises the specter of even an accurate prediction not having a practical effect.

The final thing that I think the IPCC did really well and that AGI predictions would benefit from is careful language and convention around uncertainty.

The first good thing that the IPCC does is to break uncertainty down into two categories: uncertainty about the data and uncertainty about the model. These are not the same thing. For example, the data might show a very strong correlation between historic carbon dioxide levels and historic changes in temperature, but historic levels of carbon dioxide might actually be very tricky to ascertain, so the data might be iffy. Or, the data of today’s humidity levels might be very solid, but predictions of humidity tomorrow from that data might be a difficult thing to do.

The second good thing that the IPCC does with uncertainty is to use buckets to describe uncertainty instead of using exact numbers. These buckets come in the form of common language which are defined in an appendix.

For example, part of the abstract of the latest IPCC report says “globally averaged precipitation over land has likely increased since 1950, with a faster rate of increase since the 1980s (medium confidence)”. If you refer to the appendix, this means that there is a 66-100% probability that globally averaged precipitation has increased since 1950 according to the precipitation models, and experts estimate based on ranges of data (but not exact data) that there’s been a faster rate of increase since the 1980s. Of course, the uncertainty in the data feeds into the uncertainty in the models, but they’re not the same kinds of uncertainty.

AI predictions, by contrast, do not do a good job of conveying uncertainty.

First, while most AI prognosticators have adopted the rationalist convention of stating your certainty for certain estimates, AI predictions do not separate uncertainty in data from uncertainty in models. A big part of this is the immaturity of the models, which are mostly guesswork, but this lack of clarity makes it more difficult to evaluate or improve the predictions. If someone says they estimate a 60% probability of AGI by 2043, it’s difficult to know how this probability would change with better data or better models. If someone else claims a 90% probability, there’s no way of having a productive dialogue between the two of them.

Also, AI prognosticators have a disconcerting habit of stating exact probability estimates (e.g. “60% probable we’ll achieve AGI by 2043”), and then justifying those estimates with fuzzy language (e.g. “it seems likely that…”). It’d be better if AI predictions also adopted probability buckets. Otherwise, you run the risk of pretending that your 60% probability of AGI is the same precision as, say, a weatherman’s 60% probability of rain tomorrow, when it’s really not remotely comparable.

So, that, in a nutshell, was why and how there needs to be an IPCC-like report for AGI. So, what then are our next steps?

Well, there needs to be a small group of respected individuals, ideally from both the academic and business worlds, who get together to form the bones of the organization. They will need to recruit a core writing/research team who can be paid to put the initial report together over the course of say, 6 months. Additional authors or help can be recruited on an as-needed basis.

The FTX Future Fund would be the most obvious group to put this together, given their prior efforts (and disregarding their very recent financial troubles). With $1.5 million, it’d be easy enough to recruit 15 expert writers for 6 months with more than enough left over to recruit additional authors for help. People from crypto forget this, but there are many PhDs and postdocs who would be thrilled to be paid $75k for 6 months of work, especially if they think the work is important.

And with that being said, let’s get to it, because time's-a-wastin. No time to predict and mitigate the rise of AGI like the present!

Good essay! I'd suggest though that the question IPCC tried to answer was better defined than what AI folk are trying to answer/ predict, which makes the latter harder. Which makes the clarification in terms of some common standards even more necessary.