For a long time, animals were treated a lot like machinery in America. Dogs were there to guard, hunt, and provide companionship; horses were there to ride; cats were there to catch mice. Animal food was treated much like fuel, with consumers looking to get the most bang for their buck when it came to buy. Animal diseases were like a mechanical failure: fix them if they’d be cheap to fix, throw them out if they’d be expensive. Veterinarians were like mechanics, and as long as they weren’t actively cheating the customer, they were ok.

This is not true anymore. We live in a world where people spend $50k on cloning their dogs1, the best-selling animal drugs in the world make your dog less itchy2, and a premium pet food company started in 2015 can make $1 billion/year3. Dogs and cats are members of the family and are treated as such.

The world of animal health moves slower than the world of animal sentiment, though. This is not just true of animal drug regulations, which, as I mentioned previously, are more lax than human drug regulations. This is true across the board for all sides of animal health.

Take vets, for instance. They are still far away from being the same as human health doctors. For one thing, specialization in veterinary health is rare and many vets are suspicious of it. Many vets, especially older vets, feel confident handling all aspects of a dog’s, cat’s, or horse’s health, from orthopedic surgery to dentistry. Meanwhile, many PCPs don’t feel confident prescribing drugs they’re unfamiliar with or that have any possible side effects, even safe drugs like Ozempic4.

The same is true for marketing in vet health. There’s no such thing as HIPAA for vets, for obvious reasons, and vets can legally get kickbacks from the drugs and services they prescribe, subject to some limitations5. Vets therefore have incentives to prescribe animals all sorts of unnecessary procedures and drugs, which the animal health companies are free to set up for them and profit from them.

But that’s just on the vet side. Animal health is also in its infancy on the pharmaceutical side. The vast majority of animal drugs are repurposed human drugs (probably about 90%), and most of the rest are vaccines or flea and tick medications. The number of drugs that are developed specifically for animal diseases is small, although growing.

When it comes to the pharmaceutical companies, those are also immature. There are probably only 4 or 5 animal health companies that have the capability to even develop drugs from start to finish. The rest just repurpose human drugs or reformulate old animal drugs. In fact, multiple times I have found myself in the interesting position of informing large animal health companies ($100m+/revenue) how exactly animal drugs are developed, including the relevant regulations. They literally do not know how to make drugs.

Fortunately, the research side of animal health is very well developed. There are tons of great universities working hard on innovative animal health — just kidding. The research side is almost nonexistent. Almost all the research that goes on in animal health is part of human health efforts or just basic research, like using dogs as cancer models, macaques as aging models, or Chinese hamsters for recombinant proteins (like insulin).

There are only a few universities that do animal research for the animals’ sake, and, of those, I’d say UC Davis is the only university that gets close to a human health standard. This can get very frustrating. For one of the diseases that my company is focusing on, feline stomatitis, there is only one guy actually studying it in an academic sense (and he is, of course, at UC Davis), and he is under contract with a startup who’s working on stem cells for feline stomatitis6. So, he was unable to do any consulting for my company, leaving us with zero people who could be “Key Opinion Leaders”, or KOLs, for the product.

The plus side is that somehow left me as one of the world’s foremost experts on this actually pretty common, serious feline disease7, given that I have spent more time thinking about it and researching it than almost anyone else in the world. I regularly inform both veterinarians and executives at major animal health companies about the disease and how it works.

On the other hand, this is a bit of a silly situation. For every human disease that affects more than 1000 people there are at least 20 MDs and PhDs who have spent huge parts of their career researching this disease. But a disease that affects over 1 million cats a year? There’s only one PhD who’s spending a lot of time on it, and he’s under contract.

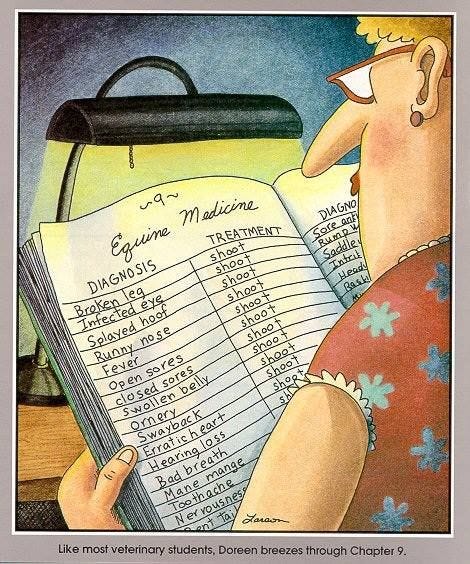

I don’t think this state of affairs will last forever. This field is growing and maturing, and regulators, industry, and academics are growing and maturing along with it. I don’t think we’re going back to the bad old days of Far Side horse medicine anytime soon. In fact, my hope (and company business plan) is that we’ll soon see better drugs in animals than humans, spurred by easier regulations.

But, that growth is still in the future. For right now, it’s still just the beginning.

This is not recommended, by the way. You are not guaranteed to get the same dog, personality-wise. Why this is would be an interesting story for another time.

Apoquel and Cytopoint, two biologics for atopic dermatitis both owned by Zoetis, selling $1.3 billion/year. For comparison, Keytruda is the best-selling human drug, and sells $25 billion/year.

Farmer’s Dog, which costs $250/month. For the record, I feed my dog Orijen, another premium pet food, which costs only $90/month. Every time he refuses to eat it and begs for my food instead I feel a pain in my wallet.

True story: a friend of mine went to his PCP to try to get Ozempic prescribed. First, they prescribed him metformin. This, of course, failed to make him lose weight. Then the PCP sent him to a weight loss clinic, which prescribed him liraglutide, which, of course, also failed to make him lose weight. This same weight loss clinic made him sit through a 45 minute presentation on the glories of gastric bypass surgery. After this experience, my friend gave up and just decided to intermittently fast, which, so far, has actually worked quite well for him. He’s lost over 100 pounds!

They also tend to do a lot of stuff in-house, like the dentistry work mentioned above, even when maybe they shouldn’t.

This is total nonsense, of course, like most stem cell stuff. I think, by this point, people have recognized that injecting stem cells into injured tissue and expecting a miracle is nonsense for human health, but somehow that approach still survives in animal health and can get the only KOL in a disease locked up in an exclusivity contract. Blame that on the immaturity of animal health as well.

The literature estimates between 0.5 and 12% of cats have feline stomatitis, which is a hilariously wide estimate that again points to the immaturity of animal health as a field. Like, seriously, if a cat has a bloody mouth and won’t eat or drink, he has feline stomatitis. It’s not exactly hard to diagnose. My personal estimate is that about 1% of cats get it in any given year, based on some back-of-the-envelope calculations and a bunch of conversations with vets.