Lessons on getting things done from Robert Moses

I think I’m probably the last person on the Internet to read The Power Broker, Robert Caro’s immense, incredible biography of Robert Moses. In case I’m not, let me give you a quick summary: according to Robert Caro, pretty much all major changes that occurred in New York City from around 1924 to around 1968 had something to do with Robert Moses, New York City’s planner. Roads, highways, parks, buildings, taxes, hospitals, city government reforms, state government reforms, Moses had a hand in all of it without ever holding an elected position.

Some of Moses’s impact was good, like almost single-handedly planning, designing, and organizing the most visited beach in America, Jones Beach. Some of Moses’s impact was bad, like displacing a ton of poor people from areas he wanted to develop. But it was all big. This makes Robert Moses interesting.

Because I’m like 50 years late to The Power Broker party, I’m not going to spend too much time recapping Robert Moses’s specific accomplishments and sins. You can read the Goodreads reviews for that. Instead, I want to focus on the aspect of Robert Moses that obviously fascinates Caro the most, and the part that I think has the most bearing on our present day times: his ability to get things done.

People who have never tried to get things done often underestimate how hard it is to do so. This is incredibly obvious when I see people slagging on Elon Musk’s business accomplishments 1 or trying to solve political problems by proposing massive changes to the economy. Systems resist being changed. People resist being told what to do. Nobody likes parting with their money. It’s just as difficult, proportionally, to the number of people, time, and effort, to build a bridge as it is to get your friends to rent a cabin for the weekend.

Personages 2 like Elon Musk or Robert Moses who can imagine and push through major projects are, therefore, rare. This was as true in Robert Moses’s time as it is in ours. Robert Caro takes pains to point out that one of the reasons Robert Moses stuck around so long, even though he had a talent for pissing people off, was because he got stuff done. Even FDR, who detested Moses and had a talent for holding grudges, not only maintained Moses’s power but actually increased it during FDR’s reign as NY governor.

So, I wanted to write up a quick list of how Robert Moses got stuff done, and what that can mean for us in the modern era.

1. Robert Moses was not afraid to piss off some people, but he kissed up to the right people.

Early on in his career, Robert Moses was an idealist. He believed in meritocracy, a government that helped the people, and efficiency in public policy. This gained Moses friends among the idealists, and pissed off the New York political establishment, most of whom were part of the notoriously corrupt Tammany Hall political organization and believed in cronyism and governmental handouts to friends and family. Unfortunately, as is generally true everywhere in government and often true elsewhere, the idealists had no power and the pragmatists had a lot.

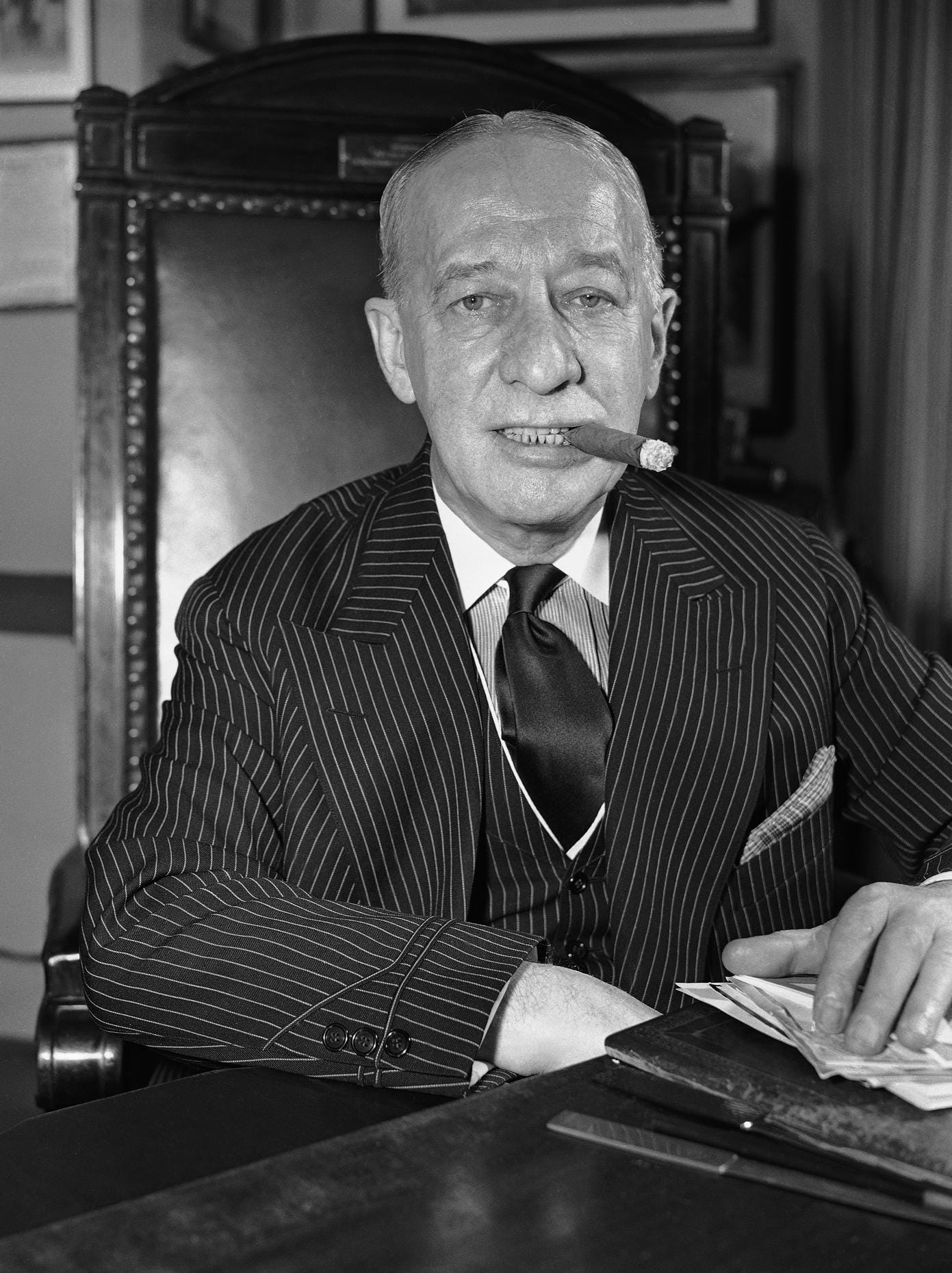

So, the pragmatic Tammany Hall squashed the young, idealistic Robert Moses like a bug, rendering him unemployable for a number of years until he became close chums with a Tammany Hall politician who was more idealistic than the rest, canny cigar-chewing New York Governor Al Smith. From Al Smith and his own time in the desert, Robert Moses learned the true skill of getting idealism to work was kissing up to the right people, as his idealism was already going to piss off a fair number of the wrong ones.

So, practically speaking, that meant turning his nonprofit’s newsletter into a Tammany Hall mouthpiece, rewriting all his proposed bills to avoid disturbing any important Tammany Hall patronage relationships or unnecessarily pissing off rich people, and being available to freely consult and write on any political topics for Al Smith. All of these actions combined did turn Robert Moses from a beautiful idealist to a dirty pragmatist, and upset many of his former idealist colleagues, some of whom had vouched for him at crucial moments. But, Moses didn’t care. Being in good straits with his idealist colleagues had landed him in the unemployment line. Being in good straits with Al Smith and Tammany Hall helped make Moses’s dreams come true.

In the modern era, as in Moses’s era, there are few people who are as idealistic as Moses and still willing to debase themselves that much or get that many of their former allies mad at them. Not many people can keep visions of the world’s greatest public park in their head while they are carrying out backdoor shenanigans to secretly screw over a politician’s rival, nevermind while getting called a devil by other idealists. But this sort of pragmatism is necessary to get things done. You just have to be careful not to lose your soul.

2. Know the rulebook and use it.

One of the reasons Robert Moses was so able to get things done for Al Smith and for FDR was that he knew the rulebook better than anyone else. This was both the literal rulebook, namely the book of laws for New York State, and the figurative rulebook, namely all the various hidden interests of the various power players in New York politics. By mastering these, Robert Moses was able to draft laws that furthered his interests as much as possible and kept important people as happy as necessary.

For instance, in his original bill establishing the Long Island State Parks commission, he drafted the bill to use a questionably legal definition of “appropriate” that dated back to an unused law from the 1880s. When New York State legislators passed the bill, they unknowingly gave Moses the power to take land from landowners and pay for it later, instead of what they thought they were doing, which was give Moses the power to buy landowners’ land by mutual agreement. By the time they realized this, Moses had already appropriated a huge amount of land to build the parkway (although this did eventually end up with a huge legal headache for Moses).

This knowledge of hidden levers and clever dealmaking is just as advantageous in the modern day as it was in Moses’s. I can’t speak too much on modern politics, because I don’t follow it closely. But, it does remind me of the clever, complicated initial structuring of Axovant, the company that made Vivek Ramaswamy rich. Ramaswamy incorporated Axovant in Bermuda, as well as Roivant, the parent company. Ramaswamy took Axovant public, but kept Roivant private and controlled by him and his family/colleagues. This allowed Ramaswamy to not only get rich off of the IPO, but maintain control of Axovant no matter what happened, and use the money that Axovant generated from its IPO to pay Roivant for “services”.

Axovant, as a company, failed pretty soon after its IPO. It then limped along for several years until it was finally discontinued. However, much of the money that Axovant generated from its IPO flowed up to Roivant and Ramaswamy, so this ended up being a great deal for the company and the man. Roivant, since then, has actually used the money quite wisely, especially since Ramaswamy left, developing good drugs in a range of areas and making lots of money off of them, in large part by more clever dealmaking. Ramaswamy, on the other hand, has used the money to try to become the Indian Donald Trump.

So, overall, it’s a mixed bag on whether Axovant’s clever structuring was good for humanity. It was certainly bad for retail investors who invested in the initial IPO, suckered in by Ramaswamy’s clever storytelling. But it’s a great example of how knowing the rules and the levers of power is a useful way to get stuff done in complex, heavily regulated worlds like finance and biotech.

3. Make visible progress

Whenever Moses would get any amount of funding or power, he would drive his people incredibly hard to make some amount of visible progress. This might be laying the foundation for a road, building a cabin, or clearing land. He did this for a few reasons:

a. It showed that there were real, concrete gains to be made from giving Moses power, in a way that was only theoretical otherwise

b. It allowed Moses to use the sunk cost fallacy, as legislators would be loathe to take away his budget (or deny him budgetary overruns) and leave works half-finished

c. It got a bunch of people actively involved and rooting for the project’s success, even if they were just bystanders

Moses would even half-complete a bunch of projects instead of fully completing one to maximize the visibility of his progress, relying on the sunk cost fallacy to get the rest of his projects finished. In other words, if each road cost $2 million each, and he had $10 million, he would drive his people at a breakneck pace to complete 10 roads halfway, then, by the time the legislature realized he ran out of money, he’d be back in front of them asking for $10 million more to complete all 10.

This emphasis on visible progress set Moses apart from other politicians of his time (or, indeed, our time). The standard politician, if given a $10 million budget to build roads, would spend the first 5 years slowly figuring out who to give money to through “condemnation” and negotiations over the road placement3. Robert Moses established his reputation as a guy who got things done by showing such visible progress, which then made people more inclined to give him the money to get more things done.

4. Go tit-for-tat: reward those who stand with you, punish those who stand against you

Moses was famous during his own time for being an exciting, demanding boss to work for. His philosophy towards his employees could be summed up something like the following:

a. Hire the best

b. Demand their best work and accept nothing less

c. Give them freedom

d. Work them day and night

e. Pay them well

This was true for his manual laborers, who he had work on 8 hour shifts, morning, noon, and night. This was true for his architects, who’d be given incredible leeway to spend as much money as possible to redesign New York City, but harshly critiqued if they made a mistake. And this was true for his surveyors, who’d be sent out into the wilderness and told to survey land and report back, nevermind who was there already or claimed they didn’t want surveyors on “their” land4.

For those who dreamed of making an impact, architects and engineers who had been held back by lesser men with smaller budgets, this was a dream job. For those who wanted free time, family life, or not to be yelled at, this was a rough time. Those who were able to stick it out, though, were rewarded not just with impact, but with all of the perks that Robert Moses could squeeze out of the legislature for them.

All this was well known during Moses’s time. What was less well known, and what was revealed in The Power Broker, is how Moses treated anyone in his way of gathering absolute power over the physical structure of New York. Those people he crushed.

Speak out against Moses’s plan for a park? Get a letter sent about you to every legislator in New York accusing you of being a bully. Refuse to give your land to Moses? Get your house knocked down. Speak out against your house getting knocked down? Get called a rich, selfish prig on the front page of every newspaper in New York.

Moses operated on a very simple principle: if you were with the people of New York, then you were with him and his plans and you were good. If you were against him or his plans in any way, then you were against the people of New York and you were bad. Moses learned enough from being crushed as an idealist to temper this strict moralism with alliances made from expedience, but it never really left him.

It’s rare to see this sort of crusading attitude in a public official, especially nowadays. It makes me think much more of our capitalist crusaders, like Steve Jobs or Elon Musk, who have that same combination of grand vision, ability to inspire loyalty, and vindictiveness. The only thing that Moses was missing was the ability to fire people on a whim, but that was mostly just because of worker protections. Besides, as Moses found, scheduling people to start work at 2 am 7 days a week worked just as well as a firing.

5. Get the public on your side

Moses had a lot riding against him at all times. He was arrogant, vindictive, and frequently operated outside the bounds of the purview of his office and even the law. This placed a target on his back that was quite justified.

But Moses always had an ace up his sleeve: the public. The public, and their newspapers, adored him. He was the man who brought roads and parks to New York. A lot of wrongdoing could be forgiven or papered over because of this, especially when Moses’s point of view on the wrongdoing would get front page and his opponent’s would get page 25.

The public’s adoration of Moses was not an accident. Besides his aforementioned strategy of making visible progress, Moses also deliberately cultivated an image of a high-minded reformer in his press relations. Similarly, he made an effort to demonize his opponents in his press relations.

This strategy paid off in spades numerous times. Every time a politician tried to get in Moses’s way, Moses would threaten to quit. Most of the time, the politician was so afraid of the backlash from the famous reformer Robert Moses quitting a project that they’d give in and let him get his way.

Of course, it’s not exactly surprising for a politician or someone involved in politics to try to sway the public to their side. It’s practically in the job description. However, Moses’s unique position as an unelected politician with unclear and ever expanding job description allowed him to use public opinion to great effect. Similarly, his portrayal of himself as an enlightened reformer above the fray of normal politics allowed him to transcend party lines in a way that would have been difficult otherwise.

6. Establish your own fiefdom

None of Moses’s accomplishments would have been possible if he had been under the control of anyone else. In fact, almost all of the above was in service, somehow, to his independence. His cultivation of powerful friends and loyal employees, his legal and extralegal maneuvering, his establishment of himself as a beloved public figure: all of it served to make him a singular entity to the greatest extent possible.

As soon as Robert Moses could, he set himself up with his own fiefdom. In his department, which was, eventually, the Department of Parks of New York City5, he set himself up with sole control of the multimillion dollar budget, including hirings and firings. To get himself to this level of control required decades of effort and a lot of clever maneuvering, including multiple laws he wrote himself and got passed through the legislature.

This culminated with his control of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority. Not only did Moses control the tolls from this bridge that he designed and got built almost single handedly, but he also gave himself the power to issue more bonds based off of those tolls, without voter approval. This gave Moses a huge budget to control by himself, about $2.3 billion over the course of his control of the bridge, which was frequently, on an annual basis, greater than the budget of New York City itself.

To find a parallel, I again have to turn to capitalism, as I really am not aware of anyone who has that amount of power in politics anymore, outside of dictators. If I was more versed in political history, this might be an appropriate time to bring in, say, Lee Kuan Yew, or even Robert Moses’s sometimes ally, frequent rival FDR. But, instead, I’ll bring in Mark Zuckerberg, who famously has structured Facebook’s stock with a dual class structure that gives him control over Facebook’s future without owning a majority of Facebook’s shares. This has allowed the Zuck to make huge bets with other people’s money, including his recent $20b foray into the Metaverse and gigantic foray into open source AI.

They say there’s an African saying that goes something like, “If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.” But, I think that’s mostly said by the slowest person on the group project. In reality, if you want to do big things, you need control of your own destiny.

As opposed to his personal failings, which are not only fair game to slag on but almost impossible not to.

I didn’t want to start another paragraph with “People”.

Having a road built on top of your land destroyed it. Having a road built next to your land made it way more valuable, assuming you wanted traffic. You can imagine how negotiations tended to go based on this fact.

“My land, soon,” thought Robert Moses.

This is misleading because he had control over a lot more of the physical infrastructure of New York City and New York State than the parks, including the bridges and the roadways, thanks to his multiple appointments throughout the City and the State.

Not the first review I've read of this book, but it might be my favorite :)

Great summary!